4. Consequences, Interventions, Punishments

Consequences, Interventions, Punishments

This section of the Classroom Management Training Module focuses on two areas. First we will look at Consequences and Interventions with three helpful subsections and a learning activity, then we will explore Consequences and Punishments and conclude with a scenario-based activity.

Consequences and Interventions

1. The CALM Model

Audio Version

Consequences and Interventions (1:55)

Click above to listen to this section via audio. If it does not play or if you would like to download it to your device, click here.

Knowing that misbehaviour is inevitable, one of the best ways you can prepare for it is to build your arsenal of skills for managing and defusing challenging situations. When an incident occurs, we need to consider first what may be causing the behaviour:

Is it an attitudinal barrier? e.g., Misconception, stereotype, label, fear

Is it an environmental barrier? e.g., Space, safety, success for Individual

Is it a programmatic barrier? e.g., Training, time, lack of resources

If there is a repetition in the antecedent (preceding) event that triggers a particular situation, we know where to make change. If we never pay attention to understanding the why or reasons behind a behaviour, finding the “how” because less likely.

Once a challenging situation arises, we can turn to the “CALM Model”: Consider, Act, Lessen, and Manage. This model is an overall framework for classroom management that seeks to minimize disruption to the group and maintain a positive, constructive learning environment.

When considering whether a participant has become disruptive, ask yourself - is this behaviour limiting the safety, learning, or enjoyment of the individual and/or others? Strategic decisions about when and how to intervene can be made when this is considered. Secondly, act only when it becomes necessary. This prevents instructors intervening in every incident; behaviour should be responded to when it is a distracting force. Next, lessen your invasive response to dealing with the disruptive solution. Be a classroom management ninja! The less you can involve or derail the rest of the group, the better. Finally, manage the environment quickly after the act. This minimizes distraction to the rest of the participants, and allows everyone to return to routines.

2. Verbal and Non-Verbal Interventions

Audio Version

Verbal and non-verbal interventions (6:48)

Click above to listen to this section via audio. If it does not play or if you would like to download it to your device, click here.

When it comes to behavioural interventions, you as an instructor can choose whether you are going to use non-verbal or verbal strategies. Can you think of some examples of each? Which do you typically turn to first, and why? Remembering the CALM model, how do these compare and contrast in terms of degree of invasiveness?

Non-verbal interventions are generally considered the least invasive, and the best first choice when misbehaviour is starting to occur. Examples of non-verbal interventions:

- Planned Ignoring: Don’t engage with or respond to the disruptive participant/behaviour (this can work well with behaviours such whispering, calling out, interrupting)

- Signal Interference: Communication via behaviour with a participant that does not disrupt others (e.g., clearing throat, eye roll, shaking head “no”, direct eye contact)

- Proximity Interference: Any movement toward the disruptive participant (e.g., standing next to them while continuing to deliver instructions)

When non-verbal interventions are not resulting in the desired behaviour, we will often switch to verbal interventions with participants. These are examples of verbal interventions:

- Adjacent Peer Reinforcement: Focuses on appropriate behaviour; reinforcement shows that it is more likely to be repeated. e.g., “I really appreciate that you put your hand up to answer this question” OR: “I see that Melissa is sitting and ready to go, oh, so is Caitlin...”

- “Are Not For”: Statements to stop behaviour, best for young ages. e.g., “Chairs are not for rocking”, “Hands are not for hurting”

- Broken Record: Repetition of the same message.

- Instructor: Doug, stop calling out answers and raise your hand if you want to answer a question.

Participant: But I really do know the answer.

Instructor: That’s not the point, you need to stop calling out answers and raise your hand if you want to answer a question.

Participant: But you let someone else call out..

Instructor: That’s not the point, stop calling out answers and raise your hand if you want to answer a question.

- Instructor: Doug, stop calling out answers and raise your hand if you want to answer a question.

- Direct Appeals: A courteous request: e.g., “Caitlin, please stop calling our answers, so that others have the opportunity to try.”

- Explicit Redirection: Give an order to stop misbehaving and resume the task they are supposed to do - is a direct order. “Caitlin, stop calling out answers and raise your hand if you want to answer a question.”

- Glasser’s Triplets: Sets of questions or statements designed to establish suitable behaviour for students. These are: 1) What are you doing? 2) Is it against the rules? and 3) What should you be doing? (to replace negative behaviour with positive)

- Humour: Make a joke or share a silly story to refocus the group (Be careful of sarcasm)

- “I” Statements: Describes the behaviour, states the effect on teachers and others, and explains the teacher’s feelings - participant must consider others’ feelings. Best when done in three parts:

- Describe the disruptive behaviour (e.g., Caitlin, you are not raising your hand to ask questions)

- Describe the effect this behaviour has on others (e.g., This means that other students don’t have a chance to ask questions)

- Describe how this affects the instructor (e.g. It makes me feel like I am unable to get on with my lesson)

- Questioning Awareness Effect: Drawing students to the attention (create awareness) of the impact their actions are having. e.g., “Caitlin, are you aware that when you call out like that, you limit the chances for other people to take part in our class?”

- Student Name: Using the student’s name when saying the intervention can draw their attention in a less disruptive way. e.g., “Caitlin, maybe you can tell us what the next instruction might be” NOT: “Caitlin, I see you were talking. Can you tell us what I just said?”

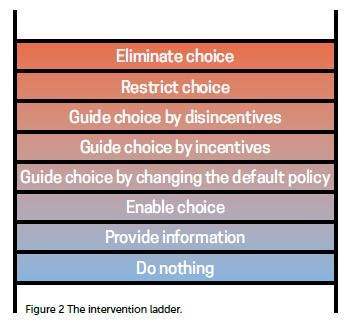

3. The Intervention Ladder

The idea of the Intervention Ladder is that instructors have a choice of increasing their interventions. At a minimum, you can do nothing when disruptive behaviour occurs. At a maximum, you can completely eliminate the participant’s choice and shut things down.

(Image Source: http://www.fstjournal.org/features/29-1/nutritional-behaviour)

Overlapping is the ability to attend to two issues at the same time, and a good way to minimize disruption to the group. Here is an example:

A teacher is meeting with a small group and notices that two students at their seats are playing cards instead of doing their assignment. The teacher could correct this either by:

- Stopping the small group activity, walking over to the card players and getting them back on task, and then attempting to re-establish the small group work, or

- Having the small group continue while addressing the card players from a distance, then monitoring the students at their desks while conducting the small-group activity.

As you can tell, the second approach involves overlapping. Overlapping loses its effectiveness if the teacher does not also demonstrate “With-it-ness.” If students working independently know that the teacher is aware of them and able to deal with them, they are more likely to remain on task.

In the next two activities, you will first complete a reflective activity on the Intervention Ladder in practice, and then work in a group to role play some interventions.

Activity Four: Using the Intervention Ladder

In your Classroom Management Workbook, or personal notebook use the intervention ladder to complete activity four. For each step of the ladder, describe what that step might look like in action (e.g., in a classroom setting). Think about when (or why) you might need to escalate to that level for each step.

| Intervention Ladder Stages/Steps (order is increasing) | What does this look like? |

| Do nothing | |

| Provide information | |

| Enable choice | |

| Guide choice by changing the default policy | |

| Guide choice with incentives | |

| Guide choice with disincentives | |

| Restrict choice | |

| Eliminate choice |

Optional Group Activity

If you are completing this training with your team in-person, try out this group activity, or next time you have a staff meeting consider doing this exercise together.

Scenario:

You have a participant who is clearly disinterested in what is going on. They continue to rock on their chair and gaze out the window, despite your repeated attempts to excite the class and change up the activities. You are both concerned for their safety (chair rocking) and their sense of belonging (not involved in group activity). Though they have posed no distraction or disruption, you decide to take action. What do you do?

Task:

Determine which intervention you will use (refer back to the non-verbal and verbal interventions for reference). Each team member will show/describe their actions to their group. Group will guess which intervention(s) were used.

Consequences and Punishment

Audio Version

Consequences and Punishments (2:20)

Click above to listen to this section via audio. If it does not play or if you would like to download it to your device, click here.

Now that we have discussed consequences and interventions we will turn our attention to consequences and punishment.

There are two main types of consequences. Natural consequences are the inevitable outcomes of behaviour and the full responsibility of the participant. Logical consequences require outside intervention (e.g., from an instructor), and should be directly related to the behaviour.

In contrast, punishments are typically not related to the behaviour that occurred. Like logical consequences, punishments require outside intervention; however, because they are not directly related to the behaviour, they may not lead to the sustained change that you are seeking as a leader. In short, punishment may not be as effective in supporting behaviour challenges as once thought.

Review the table depicting some differences between consequences and punishments below, then move onto activity five to analyze the differences in various scenarios.

| Consequences... | Punishments... | |

| Resulting behaviours | Does not develop 'escape' or 'avoidance' behaviours | Develops 'escape' and 'avoidance' behaviours |

| Resentment | Does not produce resentment | Produces resentment |

| Instructor involvement | Instructor is removed from negative involvement with participant | Instructor involvement is negative |

| Underlying concept | Based on the concept of equality (Think: tough, but fair) | Based on the concept of power |

| Communication | Communicates the expectation that the participant is capable of controlling their own behaviour | Communicates that the instructor must control the participant’s behaviour |

Activity Five: Natural Consequence, Logical Consequence, or Punishment

For each of the scenarios below, describe a natural consequence, logical consequence, and punishment that could be implemented. You can record your answers in your Classroom Management Workbook or personal notebook. A few blank rows have been left for you to identify some other scenarios you may have encountered in your own context or personal experience.

| Scenario | Natural consequence | Logical consequence | Punishment |

| A program participant damages another participant's project | |||

| A participant decides to eat the group snack early | |||

| Two participants play Minecraft while they are supposed to be cleaning up | |||

(Your own scenario here) | |||

(Your own scenario here) |

Viewed 4,799 times