2. The Content Development Process

The Content Development Process

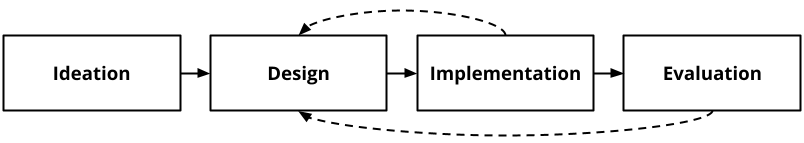

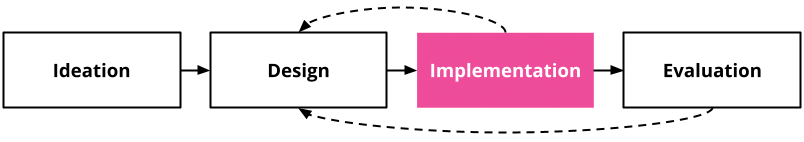

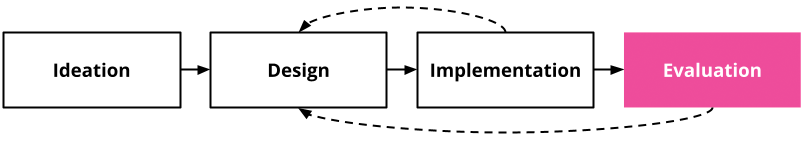

It is important to understand what kinds of tasks make up the development and use of program content. These tasks have been organized into four categories—1. ideation, 2. design, 3. implementation, and 4. evaluation. Much like the engineering design cycle, this is an iterative process with testing and cycles of feedback, leading to the best possible final product.

As illustrated, each task group flows into the next, with the output of the tasks supporting further content development. While this process can be linear, starting with ideation and finishing after evaluation is complete, it also has the potential to be cyclic or iterative, as shown by the dashed arrows circling back to the design step. This can happen after implementation or evaluation and is meant to reflect changes to the content to address any issues that may have come up during implementation or integrate feedback received from participants or other stakeholders post-evaluation.

Task group | Potential tasks |

Ideation |

|

Design |

|

Implementation |

|

Evaluation |

|

Before you begin...

While you may have a considerable amount of freedom choosing what to create for program content, there will likely also be both practical and programmatic constraints on possible activities. Constraints are often established in advance, though some might be emergent. Keep this in mind as you begin to plan and build content.

You should start the content development process knowing, at least roughly, what the requirements and program-specific details are for what you’re creating. These can help to identify possible sources of constraints and some are treated in greater detail later on in this module. These details include:

Program themes

Program outcomes

Program delivery mode and context (discussed in the later section on Delivery Environment)

Program length

Program date and location

Expected age group of participants (discussed in the later section on Intended Audience)

Expected participant group size

Length of the content in terms of how much time is available to use

Any existing content that you will be working with

These details serve to create a foundation upon which you can develop your content.

A note about safety

Creating content that is safe for participants and instructors is the foremost consideration for any content that you develop. Safe does not necessarily mean there are absolutely no risks or no possibilities for injury, just that such things have been considered and steps have been taken to reduce their likelihood and mitigate their impact or severity. Your organization and your institution likely already have guidelines in place for determining what is considered safe and what is an acceptable level of risk. Be sure to check with your team lead or supervisor to understand what procedures are in place and what your responsibilities are when it comes to developing and reviewing content through a lens of safety and risk.

Ideation

All content starts with an idea. In fact, content typically starts with finding inspiration from a variety of sources, including media (such as TV shows or movies), social media (e.g., TikTok,YouTube), other content developers or instructors, and your own experiences. While ideation can be done solo, doing it as a group means having an opportunity to bounce ideas off each other or draw on the experience of others who may have more expertise. Remember, the goal with content development is not necessarily to reinvent the wheel, but to build on the work of others as much as possible.

Ideating in a group setting is especially useful when there might be multiple developers creating content for a single program. Having cohesive content plans may help to avoid any overlap and create a program that feels more cohesive.

Reflection Prompts:

Where might you draw inspiration from when ideating for new content?

What STEM activities have you experienced? What STEM activities have you enjoyed?

What made the STEM activities that you enjoyed enjoyable? Likewise, for the activities that you didn’t enjoy, why didn’t you enjoy them?

(Optional) What STEM-related media (e.g., The Magic Schoolbus, Bill Nye, Cosmos, Neil deGrasse Tyson) can you think of? What are key aspects of STEM-related media that you think makes it appealing?

The last task within ideation is to narrow down the best ideas to one idea that you will develop into a full-fledged activity. Narrowing down ideas is a balance of the value of an idea (i.e., how good you think it will be as an activity) with the uniqueness of an idea’s execution. When narrowing down ideas, consider the other activities within the program, not only in terms of topic or subject (which is necessary to avoid duplication) but also in terms of potential structure (e.g., type, duration, location, individual or group).

Future Skills Instructor Quote - Teamwork and Collaboration

“One of the big things that SuperNOVA has trained us to do is interact with children, but also interact with other leaders in a productive manner. And that is a fundamental skill that will come in and see play in every work space. We collaborate as a team, designing all these activities, there's gonna be disagreements and discussions that need to happen, and we are given the opportunities and tools we need to deal with those. So I would say that [teamwork], and the communication skills in general are what I take from this so far. I'm interested to see what else of my training comes forward as the summer progresses.”

- Instructor, SuperNOVA, Dalhousie University.”

Design

Design tasks convert rough content outlines and ideas into detailed procedures that can be used for content delivery. This is also the point we would encourage you to engage in content stakeholder consultation, as well as pre-implementation review and feedback. Determining if consultation is necessary or advised is a shared responsibility. When developing content, you shouldn’t hesitate to raise any thoughts or concerns you have about consultation with your team lead or supervisor. Later in this section, we identify a few points at which consultation might be prudent, however you should always be thinking about the potential of your content to impact not just your participants but other stakeholders.

The upcoming section on content must-haves outlines key considerations and sections for content development that are universally important. There are also considerations that are specific to content type, that is, the broad approach to the kind of STEM education experience that will be developed. The choice of content type sets the direction that your content will take in terms of the kind of tasks, materials, and interactions that will occur. Each content type has strengths and weaknesses and may be more or less suitable based on the topic or subject being addressed and, importantly, delivery type of the program that you’re developing it for.

If you’re trying out a new or unfamiliar concept or task, testing plays an important role in helping you to confirm things like feasibility, timing, and general user experience. Be sure to set time aside to allow for testing ideas (e.g., in the ideation phase) and more developed designs (e.g., here, in the design phase), as well as any adaptations that might be necessary for a given group or delivery location.

Note: While “content” and “activity” are not strictly synonymous, they can often be used interchangeably, as is done throughout this module.

Program delivery type

The content you develop may be adapted to be delivered in several different ways, but you will typically be designing for a single type of delivery, specific to the program where the content will be used. Multiple content types may be—and often are—used within a program. Program delivery types have been summarized and described below. These program delivery types apply to both in-person and remote delivery (the implications of in-person and remote delivery are addressed in the section Delivery Environment).

Program type | Description |

Camp | Multiple consecutive instances of delivery with the same participants. In-person summer camps, for example, are often 4 to 5 full days of programming. An overarching content theme may be set for the entire length of the camp or it might vary from day to day. |

Club | Multiple instances of delivery with recurring participants, happening on a regularly scheduled basis, e.g., weekly, bi-weekly, monthly. A broad content theme might be set for the club (e.g., coding), though it is not necessary. |

Workshop | Delivery that occurs in school, after school, with a partner youth organization, or with a community partner. Usually narrowly focused on a subject or topic. Specific considerations for in-class workshop: In-class workshops take place in school classrooms. They are distinct from many other activity types in that they take place during regular school hours (as opposed to after school or during a period of time-off) and may be linked to whatever subject matter the participants are currently learning in class. They can be used to extend material that has already been addressed in class by adding new approaches or perspectives. They can also be used to expose participants to specialized content that wouldn’t otherwise be covered.

|

Community event | Participation in community events, festivals, or public outreach events. These are typically large-scale events that bring together STEM and STEM-adjacent organizations to interact with the general public. These come in many forms, including science fairs, events such as National Engineering Week, and campus open houses, among others. Participants in these events are usually children accompanied by adults, though the age groups of the participants will vary from event to event. Short, high impact content is well-suited to be used at public outreach and community events |

Content types

Content comes in many different forms, and each of these forms is a distinct way of presenting STEM subject matter.

The most common content types are listed below.

Content type | Description | Key considerations |

Demonstration | A demonstration (or demo) is a presentation of a particular STEM-related skill, phenomenon, or concept to a large group of program participants. Typically, the demo is conducted entirely by instructors, though “helpers” might be called from an audience or the audience might be consulted for decisions throughout the demo. |

|

Hands-on activity | A hands-on activity provides individuals or small groups a way to investigate or interact with STEM-related skills, concepts, or phenomena. This is often in the form of a small experiment or series of experiments that create some sort of perceptually (visible, auditory, etc.) obvious product. |

|

Mentor or role model visit | Mentor or role model visits are meant to introduce program participants to people pursuing STEM education or working in STEM fields. Typically, these activities have a description of the mentor’s personal STEM journey to illustrate a potential pathway into a STEM-related career. For more on bringing mentors into your program, consult the Mentorship 101 module at https://exchange.actua.ca/traininglist/training |

|

Facility tour (e.g., labs, plants, shops) | On-site tours are a way to introduce students to places where STEM research is conducted, or STEM skills are applied. These naturally dovetail with mentor or role model meetings on campus, and have the added benefit of those meetings occurring in the environment where STEM-related work and inquiry occurs. |

|

In-class content | See Program Delivery Types |

|

Public outreach or community event content | See Program Delivery Types |

|

Content types are not mutually exclusive and activities, especially longer ones, often end up being a blend of multiple types. Nonetheless, you will likely design your content with one or two primary content types in mind.

While you might have a lot of freedom to decide what form your content will take, and in addition to the requirements and program-specific details of your content outlined above, you will likely also be subject to a few additional constraints, such as:

cost of raw materials to use in your content;

access to, and use of, tools to work with raw materials;

logistic considerations (e.g. transportation, sourcing) of tools and raw materials;

access to infrastructure to support your content, such as electricity, water, gas, and waste disposal;

temperature and other environmental considerations; or

time available for your content during the program.

Figuring out what constraints you’re facing early on in the content development process will go a long way to ensuring your design tasks proceed smoothly.

Reflection Questions:

What type(s) of STEM activities have you experienced? What type(s) did you especially enjoy? Why do you think that they were particularly enjoyable?

What type(s) of activities will you be developing? What specific considerations do those type(s) of activities have and how do they impact your development?

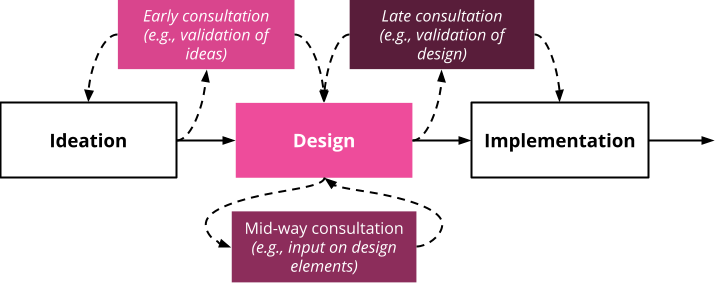

Consulting with content stakeholders

Consultation with content stakeholders (e.g., someone who may have an interest in, or is impacted by, the content of the program) may be necessary in the process, depending on the type of content. It can occur multiple times and at different parts in the design process:

When used early on, consultation can be used to validate the idea chosen from the ideation phase as suitable to be developed; or, it could indicate that there may be issues with the idea and that another one should be chosen.

When used mid-way through, consultation can provide ideas for content details, logistics, or potential resources that would improve some aspect of the activity.

When used at the end, consultation can be used to validate the design of the activity or provide possible tweaks or adjustments to content that address stakeholder needs or concerns.

Reflection questions: For each of the following scenario prompts, think about how and why you might go about engaging in consultation.

Specifically, for each scenario, try to answer:

With whom would you consult? Why?

At what point in the development process would you engage in consultation?

How might the outcome of your consultation inform or impact your content development?

Scenario 1: You are scheduled to do an in-class workshop for a Grade 8 science class.

Consultation with the class’ teacher in advance of your visit could be beneficial here to link the content of your workshop with whatever topic is currently being covered in class, or to get a sense of how much background information might be required for a topic that hasn’t been (or won’t be) covered. The teacher may also have additional insight into the needs of learners in the class and may be able to suggest or prepare modifications to make sure all their learners are supported.

Scenario 2: You are designing a week-long summer camp for a remote community.

Consultation would be appropriate here for at least two reasons: to find out if there are any specific interests or activities in the community that your content could tie into or be based around; to build a positive relationship with community members and show that you’re mindful of your status as a guest and outsider. You would likely consult first with your community contact and then work to include other community members as necessary. Consultation also creates an opportunity to include community members and practices into your content.

Soliciting feedback and review

Getting feedback from other instructors and content developers is crucial to developing an activity that is clear, engaging, accurate, and safe. Your colleagues are your first line of review for calling attention to any errors or inaccuracies in your content, or highlighting additional considerations you may have overlooked. Your organization should have a locally-developed procedure for content review that covers, at a minimum, an education or science review and a safety review. Be aware of what that procedure is, including when it takes place during content development and how long of a period is set aside for review, as you plan out your content development work.

Implementation

Implementation is where the content you designed gets put into practice. In advance of the actual delivery of your content, this means enumerating the specific needs of your content such as what logistics arrangements need to be made, and how far in advance such arrangements need to be made (if known), for optimal delivery, including:

number of instructors on hand to deliver content and any additional training or certification that might be required for other instructors

presence of infrastructure in the delivery location and any accessories you might need to make use of that infrastructure:

for electricity, be sure to consider the number of and location of plugs to plan for the necessity of extension cords and other equipment

for water, be sure to consider whether there will be running water on hand, and if so, how many sources and where they are located; and also how to manage spills

size and features of the physical space that content will be delivered in, including any special needs, such as the presence of desks or tables, movable furniture, open areas, or particular room layouts.

materials to be used in your content—how are they being acquired, transported, etc.—and whatever tools may be necessary to work with those materials. This will likely also have implications for your “Safety Considerations” section.

location availability and access, such as whether the location is in use beforehand, whether you are able to get into your location in advance to set up, and whether there are any special clean up requirements.

Implementation is also about supporting the successful delivery of your content. Content developers are often the lead instructors on the content that they develop and should be well positioned to adapt or respond to any situations that arise. When developing content for others to deliver, however, consider how much detail is necessary or appropriate to enable other instructors or facilitators to be able to use your content. Be sure to flag areas which may require additional background reading for those unfamiliar with the subject matter, delivery approach, tools, or materials being used.

Evaluation

After content has been used, it can be evaluated for its effectiveness. Your organization should have a framework for evaluating effectiveness. After implementing content, evaluation is a time to reflect on the development process and its product based on your experiences. Ask yourself:

What worked with the activity? What went smoothly? What was well-received?

What didn’t work with the activity? What rough patches were encountered?

It’s as important to recognize success as it is to recognize challenges. For both, you should try to extract and support lessons or reasons by attempting to answer the “Why?” questions, e.g., “Why was x a success?”, “Why did x not go well?”

Reflection question:

What sort of content evaluation and improvement processes does your organization have and when are they used?

| Future Skills Minds On: Now that you have reviewed the four key task areas of content development, ask yourself: at which points in this process do you have opportunities to develop or strengthen particular future skills? For example, during the design phase you use initiative skills to plan for the needs of campers. During the design phase, you might ask yourself how you demonstrated a sense of innovation and creativity. Being able to pinpoint times where you utilized and furthered your skills is helpful for building your experience in articulating your skills. |

Viewed 1,985 times