4. Content Must-Haves

Content Must-Haves

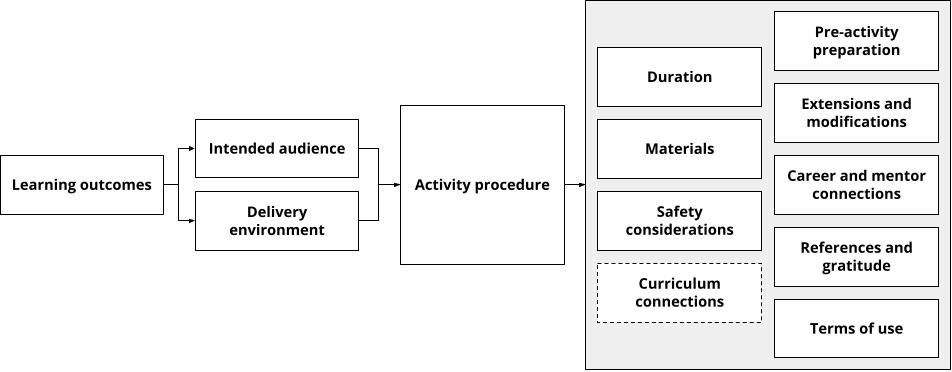

Identified below are 12 (13, if curriculum connections are included) “must-haves” for your content, elements that need to be considered when designing your content and support its successful implementation. It’s difficult to say in what order the must-haves should be addressed, since many of them can be considered or addressed in parallel. Some might even be constrained or pre-determined due to the nature of the program for which you are developing content.

Typically, though, prior to creating your activity procedure, you should establish learning outcomes for your content. You can create these by answering the question, “What are participants supposed to get (learn/experience) out of my activity?”, or, from a skill-centric perspective, “What will participants be able to do after completing my activity?” Your learning outcomes aren’t set in stone: you may decide to add or remove outcomes as your content development progresses and you make design decisions as to how you will focus your approach or get a better idea of the scope of what you’re creating. Establishing them at the beginning is still helpful as you can use them to guide your activity development.

After learning outcomes, the three sections below are what you will need to address first as they lay the foundation for the other content must-haves. They are:

Intended audience: Who will be your participants and how have you taken them into consideration?

Delivery environment: Where and how is your content designed to take place?

Activity procedure: What are participants and instructors supposed to do when they use your content?

Flowchart of typical content must-haves development order. Curriculum connections, though generally optional, may be necessary depending on where your content is being used.

Intended audience, Delivery environment, and Activity procedure are specifically addressed in greater detail in this section. Once they have been considered, alongside learning outcomes and an activity procedure, you can derive the remaining content must-haves from your activity procedure. These are summarized, with their associated key question, in the table below.

Must-have | Key question addressed | Actions/Tasks |

Duration | How long does the activity take to complete? | Break down each part of the activity and its time requirements. Make sure to include time for breaks in long activities. |

Materials | What resources and tools does the activity require? | Map out a materials list and mark down the cost of materials (especially for single- use or consumable materials that may need to be replenished), as well as any reusable tools you need to acquire and transport. |

Safety considerations | How has the safety, security, and well-being of participants and instructors been considered? What safety risks have been identified? How can identified safety risks be mitigated? | Safety for both participants and instructors is incredibly important. Write down even the smallest, simplest things to get a better idea of any potential risks involved in the activity. |

Outcomes (and, optionally, curriculum connections) | What are participants supposed to get out of the activity? What will participants be able to do after completing my activity? | Make sure your content reflects what your program is trying to achieve. Optionally (or especially, for in-school programs), you may also look at your region’s science curricula and draw connections to support your activity. |

Pre-activity preparation | What needs to be done in-advance to be ready for the activity? How far in advance do they need to be ready, and what materials are used up in the preparation? | Make sure anyone running the activity would have plenty of advance warning for what needs to be prepared beforehand. |

Extensions and modifications | How can participants continue with what they’ve learned through the activity? How can the activity be adapted for participants? How can you make it simpler? How can you make it more challenging? | Mark down possible modifications for running with fewer instructors than expected, less time, or with participants who find the base activity too difficult or frustrating. |

Career and mentor connections | What does the activity do for future participation in STEM? As with the Actua Guidelines, what connections can be made to potential future careers? | Research possible mentorship connections for those careers as a next step for interested participants. |

References and gratitude | What sources or resources were used in the activity that are not created or owned by our (my) organization? | Compile complete references to any materials or sources you used in the creation of the activity. (Refer to your organization’s referencing standards) |

Terms of use | How are others outside my organization about to use, build on, or adapt this activity? | Your supervisor or program director should have more information about this. |

Does your organization use an activity or content template? (You can also reference and/or use Actua’s activity template, which is available on the Actua Codemakers page)

Reflection Questions:

Does your organization or institution have any existing guidelines or practices that you need to consider during content development?

(Optional) Why might activity templates be useful tools for developing good content? How do they help? Do they have any drawbacks?

Future Skill Instructor Quote - Communication

“Okay, yeah. Definitely from when we're doing content development. I mentioned earlier, building skills like working with the team to create a new project and actually see it through. And then also, so I definitely would have never actually gone and created the write-up, so index all our activities. So creating documents like that, that we need to be able to be read by anyone and they need to be thorough enough, but also you can just pick it up and look at it. So I know that my write-ups... The first write-up I made looks very different than the last one I made.”

- Instructor, Actua’s Outreach Team

Intended audience

Who is the activity for?

Participant characteristics—primarily age, but likely also including other descriptors such as gender, racial identity, culture, home region, past experiences, interests, and learning needs—play a critical role in creating content that is relevant and impactful.

Your content should aim to be in the “Goldilocks zone” of your participants: within their ability to complete, while not being too easy or too challenging. In practice, this means carefully considering the capabilities and interests of your participants and balancing them with your desire to achieve whatever learning outcomes you’ve established. For many programs, the only piece of information that you are guaranteed to have in advance is participant age or participant grade level.

Other pieces of information will depend on the type of program your organization has put in place; for example, you should know (or be able to find out) if you’re developing content...

...for use in programs that are targeting specific demographic groups.

...for use in specific cultural or regional contexts.

...for a program that’s being marketed as a certain difficulty or complexity (e.g., beginner, intermediate, or advanced) or as a sequel or continuation to an earlier program (e.g., “Robotics II”).

Finally, you might have access to some additional information if it was collected during registration, such as...

...if you have participants who are experienced in your program topic (e.g., for a “Minecraft and Coding” camp, participants with previous Minecraft experience or who are expert Minecrafters).

...if you have participants with any exceptionalities and what those may be.

Designing for your intended audience

Taking your audience into account for your content means identifying and addressing the specific ways your participants’ attributes will affect their experience with your content. Questions and considerations for some of these attributes have been presented below, but you are encouraged to brainstorm, do your own research, and discuss with your colleagues other ways you can make sure your content is suitable for your audience.

Attribute | Questions and considerations |

Age | Does your content rely on previous experience, skills, or knowledge? If so, what is it? Are your participants likely to have it? Is your content age-appropriate? Not all content needs to start from zero; however, you should keep in mind that grade level or age isn’t a reliable indicator of what your participants may already know. Think of ways to check where participants are at and plan ways to bring participants up-to-speed so they can fully participate in whatever you have planned. Remember that participants’ levels of experience, skills, and knowledge exist on a continuum and that children develop at different rates in different domains. If you’re designing for an age group with which you are unfamiliar, consider reviewing resources on what to expect for that age group in terms of the level of development. In Ontario, for example, the Ministry of Education describes development in social, emotional, communication, cognitive, and physical domains and provides documents for children from birth to what they call “school-aged” (5-8 years old); for “middle years” (6-12 years old); and for “youth” (12-25 years old) Does your content involve the manipulation of materials and/or the use of tools? Many tasks will require participants to use gross (i.e., large muscles) or fine (i.e., small muscles, associated with dexterity) motor skills. These develop as children grow, though they develop at slightly different rates depending on the child. When designing your content for your audience, you will need to consider both the types of tasks that you can expect them to complete, as well as how long it might take your participants to complete those tasks. Younger participants, for example, might be slower to complete some activities; might not be able to complete certain tasks without instructor intervention; or might not be able to safely use some tools or materials—even minimally dangerous tools such as hot glue guns, scissors, utility knives, or soldering irons. Adapting the design of your content for your audience’s capabilities might mean changing how some aspects of an activity proceed—for example, having a gluing station manned by an instructor rather than independently-used glue guns—or preparing some elements in advance, such as cutting out templates ahead of time. You might also need to adapt on the fly, having participants complete a task up to a certain point, but then having instructors do the fine-detail tasks to save time. As much as possible, try to design content to maximize the amount of potential participant engagement with any tasks, even if participants may need a few tries (or an extended amount of time) to successfully complete them. Your organization should have a process in place for conducting safety reviews of content that is developed for, and used in, programming. As well, the American Chemistry Society’s (ACS) Safety in the Elementary Science Classroom is a solid and concise resource that can be used as a starting point for considering safety during STEM activities for younger participants. How long are the tasks in your content? How long do you expect your participants to maintain attention? A good rule of thumb for the attention span of participants is anywhere from two to five minutes of attention per year of participant age. This doesn’t necessarily mean that your tasks must only be 12 minutes long if your audience is primarily six-year- olds, but it does mean that you should keep in mind how much variety you’re including in what you do and what you might do to maintain or re-focus participants on the task at hand. How are you structuring the tasks within your activity? How much is a participant responsible for planning and following through? Attention is part of a broader group of skills called “executive function” skills. These are skills that are related to planning, remembering, prioritizing, and staying on task. Like motor skills, executive function develops as a person ages. This means that a younger audience may have less well- developed executive function skills and thus need more direction, reminders, or support during an activity. This is especially true for free-er form tasks like self-directed exploration or investigation or complex, multistep activities like design challenges. In terms of designing your content, this doesn’t mean that younger participants are unable to complete such activities or tasks. It does, however, mean that you may need to include more explicit instructions for complex or multi-step tasks; provide more visual aids; set clear milestones and use them to structure participant progress; or break large tasks into smaller tasks. |

Gender and racial identity | How are you creating a diverse and inclusive STEM experience? Though you should always try to show STEM as an open and inclusive space for all participants, this is especially important for programs that are targeted at engaging underrepresented population groups. Representation matters—be sure to include diverse perspectives in STEM in your planning process, your content activities, role model and mentor experiences or in lab and site tours. Consult Actua’s Gender Equity and Anti-Racism in STEM (in development) training modules for more resources on how to address gender and racial identity in your content. |

Cultural context | How are you integrating culture into your STEM experience? Culture plays a role in how participants understand and experience STEM content. When possible, you should try to include relevant cultural connections in your STEM content, whether in the form of traditional tools, environment, or practices. If you’ll be delivering content in another community and you don’t already have a community consultation process in place, you should try to develop content in collaboration with local stakeholders. At a minimum, try to involve local community members during the development process (e.g., to validate ideas) and include them during implementation as positive role models for participants. |

Exceptionalities, special needs, and other learning needs. | How can your content be adapted for participants with exceptionalities? Exceptionalities, such as physical or learning disabilities, may affect how a participant is able to engage with an activity. You should try to plan your content so participants with exceptionalities can take part to the fullest extent possible. This might mean ensuring accessible access to a lab that’s being visited during a tour; or laying out rooms and workspaces appropriately; or providing extra support or guidance during tasks where necessary. You should also check what your organization’s policy is for participants with exceptionalities and if in doubt, consult with your colleagues or manager for advice on how best to adapt your content. Consult Actua’s module, Inclusion & Accessibility: Supporting all learners, for more on how to support learners with special needs. |

Future Skills Minds On: When designing activities and planning out your delivery of great STEM content, you have the unique opportunity to hone your innovation and creativity skills. Considering how to get the key ideas in a lesson or activity across to participants and keep programming fun and engaging requires a healthy dose of imagination. We all know that to keep learning engaging, we have to try new approaches, integrate technologies, and leave room for play. When designing learning experiences for students, consider how you are bringing innovation and creativity into your learning on the job as well. For more on creativity as an essential future skill, check out this article: Why creativity is the skill of the future |

Delivery environment

Where (physically) has the activity been designed to take place?

Delivery environment refers to the intended and possible environments where your content can be successfully used. At its most basic, this might be a classroom or open space, suitable for working in small groups on the floor or at tables. More complex environments might include places that contain equipment or tools necessary for your activity, such as computer labs, science labs, or machine shops. You might also design your content to be used at-home, as part of a remotely delivered program.

When designing your content, you should consider the following questions regarding delivery environment:

What delivery environments are possible for your content?

What services or utilities are necessary for your content?

Will your content be used for in-person delivery or for remote delivery?

In-person and remote delivery

Many aspects of remotely delivered content are comparable to content delivered in-person; however, there are a few key considerations in the creation of content designed for remote delivery. The actual delivery of remote content (i.e., the implementation phase of that content) is its own topic that we have covered in detail in another training module (Remote Delivery, in development). Here we will focus on the design decisions that you will have to make during the development of your content.

What kind of remote content?

The most important distinction for content delivered remotely is how and when participants and instructors engage with each other. The two ends of this spectrum are:

Fully synchronous, where participants and instructors attend an online session together, at the same time, similar to how participants would attend camp during the day; or

Fully asynchronous, where participants would independently access content, potentially at different times, without an instructor or other participants present.

The content you will be developing will tend toward the fully synchronous end of the spectrum, or at least contain some synchronous elements (i.e., hybrid, a mix of synchronous and asynchronous content), though entirely asynchronous activity-kit style content is a possibility. There are a few considerations that are unique to remote approaches to delivery that need to be considered when you are designing your content. These are summarized below.

Consideration | Implication | Example |

What kind of additional support will your participants need? | In the vast majority of in-person delivery scenarios, instructors are on hand to support the needs of participants as they engage with content. In a remote delivery scenario, while instructors are still present for support, they are limited in what they are able to effectively help with. |

|

What materials are needed for your content and how will your participants get them? | Remote content adds the additional challenge of how your participants will get whatever materials and tools are necessary for your content. Tools for working with materials also need to be established well in advance, since you will most likely not be distributing them with the materials. Keep them simple. Participants should already have them on hand. If your materials will be part of a larger package of materials being sent out for the program, you also have an opportunity to include additional supports with your materials, such as a copy of step-by-step instructions. These kinds of supports can help participants get themselves unstuck. |

|

How long will your sessions last? | When designing content for remote delivery, keep in mind how long participants will be at a screen. Remote delivery of content does open up the possibility for more flexibility with the timing of how content is delivered. Care needs to be taken, though, to ensure that participants are able to remain engaged and are adequately supported. |

|

Activity procedure

What is the process for doing the activity?

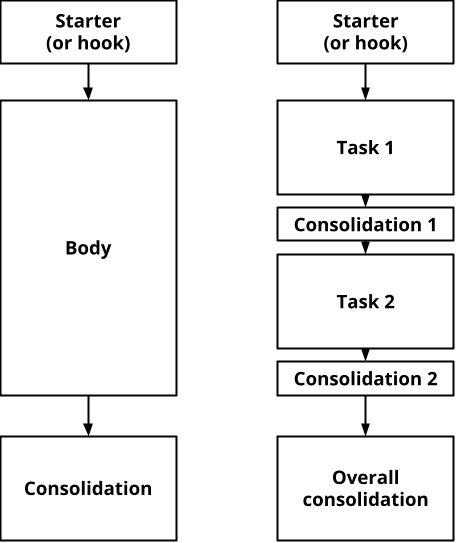

Your content will not be the same as a teacher’s classroom lesson plan—especially in terms of outcomes—but they do have considerable overlap when it comes to pedagogical approaches and structure. The basic activity procedure section is divided into three parts, the starter or hook, the body, and consolidation (adapted from Savage, p.26, 2014) are listed and described below.

Simple and complex activity structures

Section | Description |

Starter | The starter, or hook, is the part of your content that should help participants get interested in, and engage with, the subject of your content. On top of sparking interest or curiosity, the starter is also a chance for you to introduce the body of your content and establish pace. Both of these are important for a positive participant experience: laying out what you will be doing and also how you will be approaching it. |

Body | The body is where the majority of your content takes place. Here are a few points to consider for the body of an activity:

|

Consolidation | Consolidation is a chance to reinforce key messages or ideas from your content as well as provide a time for conclusion and reflection for participants. This part of the activity can be used to wind-down and re-focus participant energy towards future content. If not already part of your activity, consolidation is also a good time for sharing or showcasing participant work, discussing challenges (e.g., “What did you find difficult or hard to do?”), and suggesting or brainstorming strategies for overcoming challenges. Consolidation is also important if future program content is built off of knowledge or skills addressed in your content. It is a way to get a sense of where your participants are at—and what they enjoyed. |

This basic three-part activity procedure structure provides you with a starting point for the design of most activities. While it’s simplest to start with one major task for your activity, you might find that having multiple small- to medium-length tasks would better suit the topic or phenomenon that you’re addressing. In such cases, keep in mind what each section contributes to the overall participant experience of your content. You might, for example, consider including small consolidation periods between your tasks. In the absence of compelling reasons to not include a part, you should aim to follow this three- part structure as each plays an important role in ensuring a positive, and educational, experience for your participants.

Viewed 1,873 times